JAMIE MARTINEZ

Interview published August 18, 2022

Jamie Martinez is a Colombian-American artist who immigrated to Florida at the age of twelve from South America. He attended The Miami International University of Art and Design then moved to New York to continue his fine art education at The Fashion Institute of Technology and The Students Art League in NYC.

Jamie’s work has been featured in multiple important outlets like a half-hour personal TV interview with NTN24 (Nuestra Tele Noticias, a major Spanish TV channel) for their show Lideres (translation leaders), Hyperallergic, Yale University radio WYBCX (radio interview), Whitehot Magazine, Good Day New York (TV interview), Fox News (TV interview), The Observer, Whitewall Magazine, Interview Magazine, CNN, New York Magazine, Newsweek, The Daily Beast, Bedford + Bowery, and many more. Martinez has shown in Berlin, Brussels, Spain, Russia, Canada, Miami, California, and numerous galleries in New York City including The Queens Museum, Petzel Gallery, Galerie Richard, Whitebox NY, The Gabarron Foundation, Flowers Gallery, Elga Wimmer PCC, Foley Gallery, Rush Gallery and many more.

He is the publisher of Arte Fuse, which is a contemporary art platform focused on art shows that are currently on display, interviews, and studio visits with today’s top artists from NY and all over the world. He is also the founder and director of The Border Project Space, which was recently featured in Hyperallergic’s top 15 shows of 2018.

Hi Jamie! Thanks for joining me for Mint Tea. To begin, what’s your favorite tea? If you don’t drink tea, what kind of coffee or drink do you enjoy the most?

I drink here and there some green tea and iced tea. But I'm a big Italian espresso lover in the morning, sometimes in the afternoons. I'll do espresso in the morning, to get me going, and then if I'm drowsy, because I usually come to my studio after work, I do another one to get me going after work.

Could you tell me about your background and your practice?

I am Colombian, born over there in Ibagué, Tolima, which is between the two major cities in Colombia. I am Pijao tribe, not that I was raised on an Indian reservation over there, but the tribe from our town is called the Pijaos. They really had no language, just left mostly clay vases and sculptures for their history. I moved to the United States when I was around 13, to Miami first and then to New York as soon as I finished school. I've always wanted to be in New York. I was in Miami for art school, did Art Students League here and spent some time at FIT, and that's pretty much it. Then I just started making work.

Right now I'm focused on paintings and clay sculptures, kind of telling a story. I've been doing air dry clay for about two years making the sculptures, and always have been making paintings, but it's two different animals really. I love painting, painting is great. You can you can do anything in a painting, anything is possible. Sculpture is limited. It’s just two different things. So working on them together, I can tell my story better. I'm really into stories. And due to the research that I'm doing for this work, my art should have a strong backbone. Really it comes from almost archaeology. It's also a lot of research in history.

What projects are you working on right now?

I have a group show on 132nd Street in a park outdoors in about two months. It’s up for three months or more. I just started working on those outdoor sculptures – the same thing, clay with spells. I'm going to paint them, but the thing that I have to figure out is how to seal them for rain. So those I'm working on. Everything with the clay sculptures is really about asking for permission into different dimensions. My paintings, I want to tell a story that goes along with the clay sculptures almost, as in the clay sculptures being part of the paintings that almost come out of the paintings. I'm actually just starting to get back into painting heavily, and it's great. So I'm working on about three to four paintings right now.

I like to find something that happened in the past, and then that kind of leads me into the work itself. But the main and most important thing for the sculptures is lots and lots of researching history, lots of history. And then through that history, when I find that wow moment, because history is just so beautiful, I use that as a seed, kind of like plant a seed with the research and history. And then I let the plant, which is the art, grow itself and take me where it wants to go. I don't really make the work, like you said, “What are you working on?” Now, of course, I'm physically doing it, but I'm more interested in a higher force telling me what to do. So eventually, I would like to get to the point where I'm not even making the work, even though I'm physically making it, and it's coming from somewhere else, something higher, something better. Visions, history, things that happen, ideas. And then I do a lot of asking, So say, for instance, I'm going to do a new spell, a new sculpture, I always want to ask, and I open up myself through meditation to get that seed. I'm looking for that seed to plant from somewhere else, and then kind of nurture it, and make it grow into an artwork or whatever it is – I’m not even sure I'm making art at this moment.

Jamie Martinez, “Permission to Breathe without my Lungs in the Underworld,” 2021, paint, ink, oil pastels, spell, and wire on clay, 25 x 14 x 6 in.

Jamie Martinez, “Permission,” 2021, paint, ink, spell, and scratches on clay, life-size, 14 x 5 x 4 in.

Jamie Martinez, “Permission,” 2021, paint, ink, spell, and scratches on clay, life-size, 14 x 5 x 4 in.

I am the most familiar with your clay sculptures and installations. Can you talk about how and why you choose to work with the media that you do?

Clay, first, is great to work with. I mean, it's just so fun to mush and just move around your hands and it feels like just great, great interaction. Also, working with clay is great because it feels like you're working with the Earth itself, part of it, so you're dealing with that. So I like the way it feels, for clay specifically, the way it feels on my hands, I like the way it hardens, I like the way it reflects the Earth itself as making work from it. And when I get into my clay sculptures, it really is because my new work involves sometimes even taking physical objects into the afterlife, so I'm covering them with clay, which is kind of like burying them and trying to take them into something else. And it’s very natural and a lot of Native Americans used it, so it goes perfectly with what everything I'm doing now.

Tell me more about the objects that you're taking to the afterlife.

So my latest sculptures, all of them started with the hands first, which are two hands with Mayan spells on them where I asked permission to God A – God A is one of the Mayan gods, one of the main death gods from the Mayan culture – I asked sort of through meditation, how would I ask a higher power to get access into the underworld. And that's where the meditation comes in, and then I get some sort of vision, spell, or poem in a way, write it down in English, sometimes in Spanish, and then I'll translate these in Mayan glyphs, as close as I can, because Mayan glyphs are very complicated. I work with some scholars, one of the one of the top ones, and even he has trouble with it.

So it's difficult, but it's a perfect way to listen to the work itself, and combine with it, and put your soul into it and your heart and your belief. Because I believe that art can take you somewhere. And more importantly, all of these works, especially the sculptures are made to ask permission into the underworld, the afterlife, and we don't even know if those exist. These are just precautions. I believe they exist, through visions I’ve had, but nothing is one hundred percent. So for instance, one of my new works, I have a machete, it's actually a Japanese machete, and what I did was put a spell on the machete itself with my names and asking it to come if I need it, in case I'm getting in trouble. And then what I'll do is I'll grab the air dry clay and put the clay on top of it, let it dry, and then put another spell on top, so there's two in there. So it's kind of like almost burying the object itself, to see if it could come into transition with me into the unknown.

And that's what I do. I like to use art as a tool to protect me in the unknown. That's exactly what I'm doing, nothing else. Not really making anything for me to show as art, it's really has to do with that transition into the unknown. I couldn’t give a crap if I show anywhere or sell it. I'm not here to decorate your house. You got the wrong guy for that. I might be here to haunt it. But I'm more are interested in just letting go of everything I believe in and letting or take me somewhere because that's what everybody did in the past. Every single culture, the Chinese, the Indians, the Egyptians, the Mayans, they used the art itself to either show that they were here, what their life was, but more importantly, the kings, they were using it for protection into the unknown. Like the Chinese guy who got buried with a thousand clay soldiers, that's what I'm trying to do. Let it take me somewhere, not me take it somewhere. And I come in peace to wherever we're going, let me start there. I'm not starting no trouble. But another way to look at it is precautions. What if I get in trouble, I'm going to be ready. I'm not messing around. The whole point of art for me is to make sure I get to the other side, just like all the cultures. That's why I do the research.

Jamie Martinez, “Permission to Hear my Heart Beat in the Underworld,” paint, ink, wire, and spell on clay, 12 x 8 x 4 in.

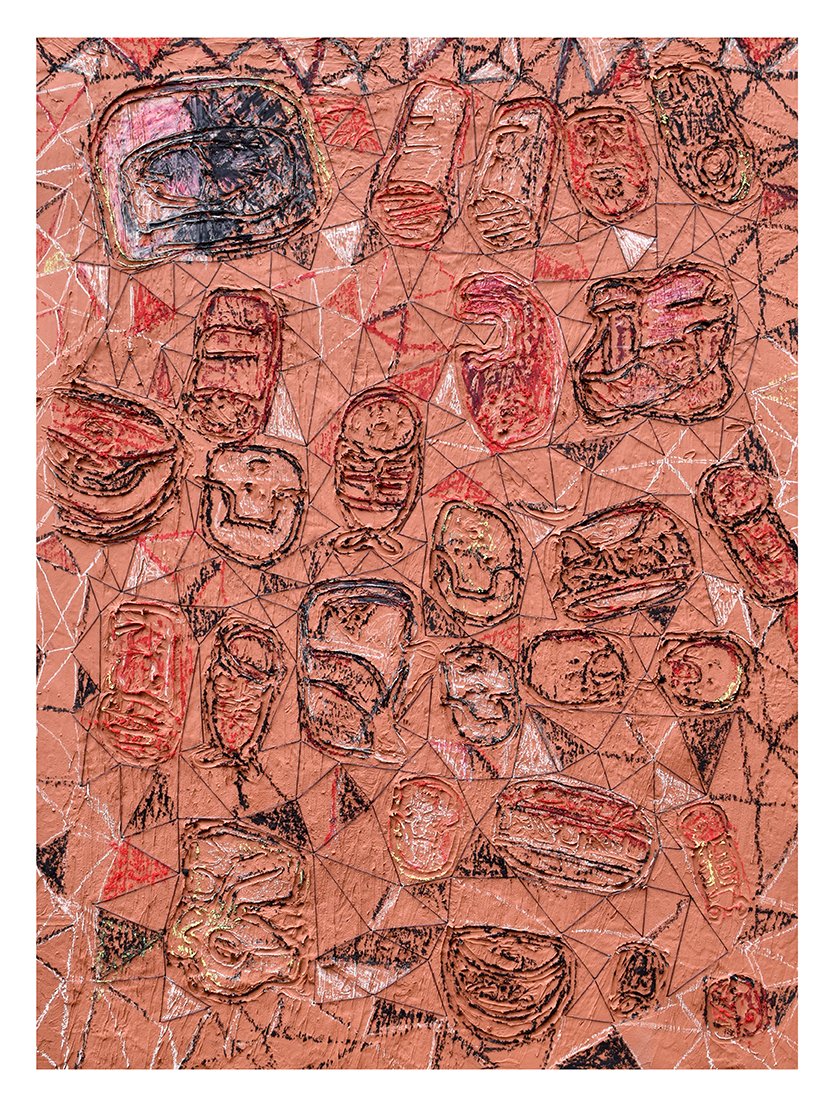

Jamie Martinez, "Permission 1," 2020, carved caulk, paint, spell, oil stick, pastel sticks and embroidery on canvas, 18 x 24 in.

Jamie Martinez, "Vision Serpent," 2020, thread, paint, ink, and scratches on clay, 7 x 4 in.

Jamie Martinez, "The Journey," 2020, carved caulk, paint, oil stick, pastel sticks and embroidery on canvas, 18 x 24 in.

What is your creative process like?

For the sculptures it’s different than the paintings. The sculptures are straight up questions. For instance, I'll give you an example of a new one. Say there's no food in the underworld, or wherever we're going. So in that one, I have to ask myself, and I do a meditation to some higher force to tell me what would be the best way to ask this world for this. So for instance, it will give me kind of an idea or something will come through that meditation. Meditation is very draining. It’s not easy. Like, it's not fun to do, because it's so draining because you just open your brain or your soul up for anything to come through – not just positive things, negative things can come through. But it all starts with the art. So if I want to do something, I'll ask myself, “How should I ask permission for my hands into the underworld?” and I meditate and meditate and something will come up, some kind of idea. And then that idea will lead me to a spell or a poem – in a way, same thing, sometimes. And then I will translate that using the Mayan gloves, now. So it's more like the idea is given to me, and it's a seed, and then I plant the seed and nurture that flower to become part of it. But the work, I mean, it is mine because I am saying, “Okay, how would I ask for it,” but it's really coming from the other side. It's more about listening to the art itself, than about me controlling it, because you can't control it, believe me. You can try. The paintings are a different animal, where once I figure out what I'm going to do, I do look for images that I can use. They don't come through as clearly, and so when it comes to the paintings, I do need to find something that supports the message given to me, to try to translate that into a painting.

Can you talk more about how you conjure up the spells inscribed on your sculptures? What is the inspiration for the hieroglyphic writing style?

First I started with the Egyptians, so I used a lot of spells that were already made. Most of them from Ani’s Book of the Dead, which is a big piece of the Book of the Dead. Ani used to be a merchant in the Egyptian civilization, so he had a lot of money and he paid for a 70 foot papyrus spell that's in the British Museum right now.

So you started with Egyptian. But now you're with the Mayans, but you're also creating your own spells.

Yeah, my own spells in Mayan hieroglyphs. And they're still very immature, I almost think of it as a child making these spells. Because I'm learning the language and I'm learning how to do spells. A better way to put it is, think of it like soup: I'm making soup here, but the chef can't cook yet. He's learning how to cook, and he's still a kid chef. So very open, very pure. And just kind of like, put some meat and potatoes and there's something there. Same thing with the spells. It does matter what I'm saying in the spell, but it also has to do with the sculpture and what I put in it. So one of the best ways to look at it, I think, is that I’m making a kind of soup that takes a long time to even cook, itself. So a lot of times I don't show these works on the internet or anything until they're ready, they're cooked. If I put a spell on a clay sculpture, it’s got to cook, it’s got to cook for at least a couple months to have anything. Because a spell is really creating some sort of energy field around it, through the spell, through the clay, into something more than just an object – to have some sort of power in a way. And it's great, because it takes a lot of time.

The beautiful part is you get to learn more about Mayan glyphs, and when you start putting it together, it's great. It’s just great. And I have shown some people that know that know the Mayan culture, and they're very impressed with what I'm doing, not being a scholar. It's really based on syllables. There's over a thousand glyphs, they have an alphabet, but some letters are not in there, like R and E. So you have to go around them. For instance, if a letter R is involved in one of my spells, I use the glyph for “are.” There's no D, so sometimes I try to use “day” or something that says “D.” You have to fill in the blanks, but they do have an alphabet, just like us, in a way, just missing a couple letters.

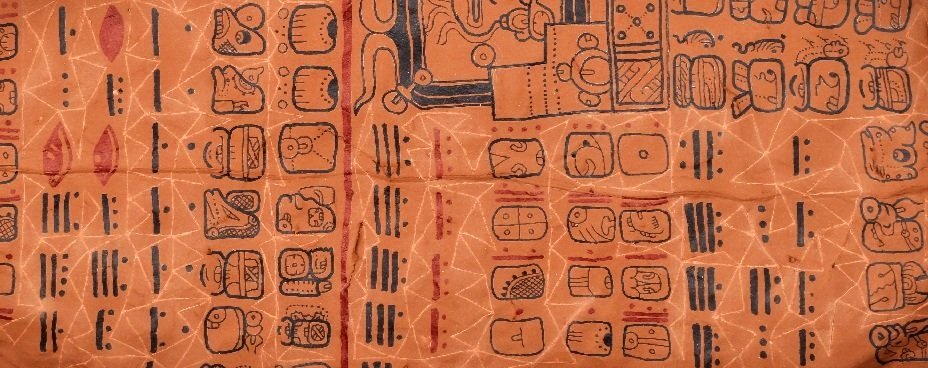

Jamie Martinez, “Dresden Codex Leaf (1–4),” 2020, paint, ink and scratches on clay, 24.4 x 10 in.

Jamie Martinez, “Dresden Codex Leaf,” 2020, paint, ink and scratches on clay, 24.4 x 10 in.

What inspires the images behind your paintings and sculptures?

At this moment, I'm going through the Dresden Codex. I'm using all the Mayan books, just a lot of research, I'm using everything they've given. I'm just grabbing the images from their books. There's only a couple left, there was a priest who burned all of them. We're missing a lot of work, a lot of work. Which is very sad, because we could see their whole story. So for the paintings, I use their images, animals, exactly what they use, copying it exactly. Sometimes I'll grab a jaguar from one of their books, and then I mix it with something else. The idea does come front them, but I do change it a bit, because I don't want to exactly do it as a painting sometimes, it depends. That depends on the work because I try to listen as much to the work as I try to make it, so it really just takes me somewhere. So I grab an image or images and I keep them around, and then start playing with them. But eventually those are gone, and eventually the painting takes a life on its own, the seed starts to grow, and the plant comes out. And that's the work, through art itself, organically let the art evolve itself, but you plant the seed. So plant the seed in a painting, and then the finished product may be completely different. Because there's a lot of back and forth, I go in there and take some out or put some in or scratch something in there. And follow that process until the painting itself tells me “Hey, hey, this is it.” Until I get to that part.

Can you talk about any imagery or symbols that you like to work with?

Sure, right now, a lot of animals, because a lot of Mayans use that. A lot of jaguars. A lot of ravens, because that's my spirit animal, that's who I really am inside, and that's something that I'm trying to hopefully transition into the underworld with, like, I should be able to access that part of my spirit animal. I'm also a raven in the Native American horoscope. And since I was little, I've always been a little obsessed with death itself, as a beautiful thing, not as a negative thing. It's just a part of life, and of going somewhere after this world.

I had a near death experience. Well, a couple, as a child, so I don't remember these. The big one came when I was playing with my brothers. I just fell on my face and turned blue. My mom thought I was dead, so she took me to the hospital and they found an air bubble in my heart, on the left part of it. I do remember just going to the hospital all the time. My mom went through some Colombian spiritual doctor to try to open up a gate to help me, and she also gave me a small statue of a doctor and saint named San Gregorio. He's a Venezuelan saint that died helping the poor. Every night, I had to take a shot of water with his statue in there, and then the leftover water I would place or pour over my heart or my chest, every night, as far as I can remember. Then we went to Bogota to get the operation, which was open-heart surgery, with a 50/50 chance of survival. I knew I was in trouble, because as a child, you don't know you're in trouble, but I knew I was in trouble the day before the operation when my mom took me to the Oprah of Colombia, a guy called Pacheco. I was the sick kid, they were giving me gifts, I was on TV. And I was like, why is he so nice to me? And the whole time, the cameras were on me, and I started to realize that something isn't right, like I was the sick child you see in those things, and this kid's gonna go soon. All right. And then so the next day, I stay with my mom. And what happened is, in the middle of the night, I woke her up, and I was like, “Hey, there's that TV guy. You keep telling me to drink water, too.” And she was like, “What the hell are you talking about?”

What happened was, I went for the operation the next day, and the doctor is like, “Guy’s cured,” and I never really get sick. I've had great health, and I don't know, I feel blessed. Maybe it was the reason that I had to have a journey to America and to do all these things that I'm doing, maybe that's part of it when you get a second chance of at life. And during all that, I had a really bad night where I pretty much saw death as a child. I was hallucinating, and that's when I kind of saw light in darkness. There's darkness, and then there's light, just like everybody says. Dark first, obviously you're leaving this world, and then there's beautiful light. That's what I saw. But the whole process is not scary. I was never scared, and I've never been scared of it. So I kind of want revenge in a way because death came for me at such a young age that it didn't come for a man, it came for a child. I took it very personally. So now I'm ready, and when it comes, we will see what happens, because I'm not a kid anymore. So that’s why I just want protection.

That's another reason I called my gallery “The Border.” Not only immigrant borders, but death is the ultimate border. So I plan to open it in the afterlife, once I cross over, and have shows, and we'll see.

Jamie Martinez, "Protector of my Heart as I Enter the Cave 1," 2021, acrylic paint , pencil, pen, spell and oil pastel on canvas, 18 x 24 in.

Jamie Martinez, "Protector of my Heart as I enter the Cave 2," 2021, acrylic paint , pencil, pen, spell and oil pastel on canvas, 18 x 24 in.

The title of your “Six Protecting Spells” series suggests that there are multiple layers of the underworld. How do you envision the afterlife at this moment?

Very simple: darkness, then light. However else however you want to put it, think of walking into a dark room: that black. That's it, and then walking into a light. The dark is scary, for sure, because you don't know what it is. To me, it's pretty much your soul leaving this world, or you just closing your eyes. It's dark, but there's clearly light after there, for sure. Just like everybody says, going back for centuries. That dark and then light, and then who knows after that, but I'm always looking for the light. The conversation gets real strange after that, because if there is an afterlife, which I believe there is, then you can never die. Can I die again? No, obviously not. Because then there is probably another afterlife, right? So it's complicated, yeah…

How many spells should we have before we go to the afterlife?

I just try to prepare for things. Say for instance, what if there's water? I have a spell for that. I have a spell where I become an octopus, and I can get out of anything, and I can breathe. They're very intelligent. What if we get attacked by bad demons, I have an army of things that will fight that. What if there is no food in the underworld? I have a spell where I'm bringing a knife that I might use to hunt. We might have to cook… So it's almost like asking yourself a question. What if this happens? What if it rains tomorrow? I need an umbrella. So that's a spell, right? Even in this life, what if I'm traveling, I get stuck somewhere, and I don't know where I am? I need something. I'm always thinking of ways that things could go wrong and how I can solve that problem. But ideally, it should be a smooth transition because I almost went through. It should be a very simple smooth transition, no issues, no fighting, no anything. These are only just in case, or what if I get in trouble. That's it.

And asking for permission, forgot about that. That's the most important thing before you enter anything, asking for permission. You can’t enter my house without asking for permission. “May I come in?” Absolutely. “May I call you?” Sure. So same thing going into the unknown, “Can I come into your dark room?” And whoever is in charge, I’m asking that question. He might say no, so I'm still going to come in my way. I got my own backup. But I'm asking first, you know, everything is always asked first. Very humble, not just asking, offering things to them, to show them I'm really for real. I'm not trying to come into your world, because no energy is going to let you come in there into anything there. It's just like anything you go new into, you might have to earn your way into it. Or not. Ideally, like I said, I think it should be a simple, smooth transition, where next I'll be throwing parties in the afterlife, in the positive way. But just in case, there are spells for water, demons, fights, how to outsmart demons, how to protect my heart. It's all about protecting your heart, nothing else. My heart has to have a smooth transition, which is what the Egyptians believed, and obviously the Mayans. Protect your heart and follow your heart that has to go through into the afterlife. Whatever happens there happens.

Jamie Martinez, “Raven Self Portrait,” 2021, paint, ink, wire, and spell on clay, 11 x 5 1/2 x 6 in.

Jamie Martinez, “Metamorphosing into an Owl,” 2020, paint, spell, ink, and scratches on clay, 3.5 x 2 x 3 in.

Jamie Martinez, “Metamorphosing into an Octopus,” 2020, paint, ink, spell, and scratches on clay, 9 in round.

I often see depictions of animals in your work. If you get to take one animal with you to the underworld as your companion, which one would it be?

The raven, and I don’t have to take him. He's inside me, so it's already there. More importantly, it's about how do I learn to transition into that animal? Not just bring it, how do I turn into it? Which is big in Mayan culture too, how to take on the spirit of an animal – of your animal, the animal that speaks to you. For me it’s a raven. I'm a bird, I go to the air.

What are your favorite colors? Do they find their way into your artworks?

Yeah, for sure, and sometimes there is experimentation that that goes along with it. You know, as a painter yourself, sometimes it just doesn't work. No matter how much you want, it doesn't work, and you have to try another color or take it away? Yeah, so the colors work themselves into my work. And right now I'm really into warm colors, the warmth aspect of them, not the cool aspect of all colors. I like a lot of purple and blues. The warm purple and the warm blue, even though they’re cool colors.

Is there a new medium that you would like to try or to work in more?

Yeah, virtual reality. I did one installation two years ago at the New School. It was a beautiful three month show. I did it with another artist, so she did the VR. And it really was just an amazing experience because the VR installation was based on the Ani’s Book of the Dead. And when you put the mask on, you would go into the afterlife, you would die, so it was training you to die. Then you would go into the underworld and you would meet Anubis and he would judge you, and that's where the VR would end. So in VR, you can do a lot, especially since I'm trying to tell a story, it can really tie the whole thing together. The sculptures with the paintings, paintings being more of a storyboard, sculptures being almost as the items in the story, and the VR, I guess you could really tell the story.

I asked in a meditation to see what would help me open this gate or this portal, to tell the story of Ani, and curtains came to mind, and projection. So I came up with a way to make them float, and then the projection went on them, and when they would move, it was very mystical. I put some glow thread and I did a triangle on the bottom with the floating fabric to kind of open a gate. But all this was given to me during a meditation, and then I drew it out. I think that's one of most my most important works. I'll tell you the truth, as soon as I did that, I took everything off my website, all my past work, and I just started over. So in a way, that show really changed my life, because that's where the first portal into the underworld came. And then that opened up the gates to everything. After doing a year with the Egyptians, I moved on to the Mayans, and it's the same thing. I mean, they're all always trying to get into the afterlife. Same exact thing. They were always trying to train themselves in this world to transition into the other world.

Jamie Martinez in studio

Where are you located now? Do you think where you are located influences your practice?

I live in New York City. New York has been a dream to live here. I'm already living the dream, coming from another country, and as an immigrant, there's nothing better than being in the biggest city in the world from where I came from. To this day, I'm still in awe of how much I've accomplished, and the same with my family. We're all very grateful for that wonderful opportunity to come into a new world. And America is great, man. I love Colombia, but I love New York and America a thousand times more. It's just been so good to me. America is just great. Dreams can come true, and it's a it's just a beautiful country. And also that has to do with my work, because I'm trying to do art through the point of view of the artist being here, as an as an American, because I am an American. I'm an American citizen, I've lived here my whole life now.

How do you stay connected to your community?

Through art and surfing. I'm a big beach guy. But mostly art – I believe the art community is amazing. That's also one of the great perks of being an artist. All my friends, all the people I know, the shows we put together, the benefits, the events. I'm big in organizing and ganging people up in a way that we're stronger together, using art, and it's great. The art community is wonderful. I think that is the best part of being an artist, almost. It's nothing to do with fame, fortune, or who's who, more like just a whole bunch of creative people really seeing each other's work and living life through that community. Being part of the artistic community is very special, and I would not change that for the world. Lucky me.

Tell me more about Border Project Space. How did it begin?

So that began when I was at home, and Mr. Trump, who just became president, all he was doing was just bashing immigrants. He was already president and just every day he was just bashing. I was like, enough. I had the money, so I'm like, “I'm gonna open a place called The Border and I’m gonna put immigrant artists in.” And the reality is, if it wasn't for Trump, I would never have The Border, for sure. So at least I have to thank him for that. It had to be a physical reaction to his words, because he's just talking trash, he's not doing anything. And being an immigrant, I'm like, “Are you kidding me?” Some of the baddest artists are immigrants and it’s like, we don't have enough of a hard, hard routine to become a normal American, now we have to be an artist too? So I respect that journey and that dedication and it's tough. It's tough to be an immigrant, period, here, never mind being an immigrant artist. But it's very tough, because speaking for myself and hanging out with mostly immigrant artists, just for us to become legal was a nightmare. Never mind being an artist, just to become legal so I can stay here, not go back to a country that I don’t know. So it's important that art can still be used towards that.

Jamie Martinez, "Raven Self Portrait," acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 12 x 12 in.

Jamie Martinez, "Snake boy with Cat," 2021, chalk, paint and oil stick, oil pastel on canvas, 24 x 24 in.

Jamie Martinez, "I Am One with the Jaguar, 2021," Carved caulk, paint, oil pastels, assorted feathers, 24 x 24 x 1.5 in.

Tell me more about Arte Fuse. How did it begin?

Arte Fuse? Wow, it's been… I can't remember when I opened, I think 2010. I started just with reviews. In a way I wanted to meet people and get to know the art world, I thought it was a good way. Because art is difficult, it's difficult to get into this. I mean, anybody can draw and stuff, but it's a lot more complicated than that. So it gave me a way into not only what's really happening, galleries, meeting people, and to really get into the into the art itself. I also wanted to help people with reviews for shows that I like. So it started with reviews, but now I'm doing mostly video on YouTube, which is doing very well. I'll do a review here and there, but I do mostly photo stories of shows I like.

What's your favorite tool?

My hands, and definitely paintbrushes, for sure. There’s something special about paintbrushes. But my hands, when you're playing around with the clay, it feels so good. It’s so relaxing, it’s like a meditation on its own, where you're actually talking to the dirt itself because you're playing with it.

What is the space where you do your work?

In my studio in Dumbo. I even make some at home too. When it comes to my studio I like to not use any kind of technology. I just come in here, no phone, and muscle out a couple hours. I don't do more than three hours because I think it can start damaging the work. I'm also trying to make work faster and simpler now, taking things away. But I also make work in my home in Midtown and I just bring it here. I do a lot of little clay sculptures over there. While I have downtime, I try to stay away from TV and stuff.

Jamie Martinez, “Dresden Codex Leaf,” 2020, paint, ink and scratches on clay, 24.4 x 10 in.

Do you have any rituals that help you get into the zone?

Yeah, absolutely. First and most important, it starts with research. Once you find that seed, or that moment where you're like, “Wow, imagine the moment the archaeologists found the Chinese emperor who got buried with all those clay soldiers. Imagine…” That's where it starts, when you're like, there's the seed, grab that seed. Then I'll do some meditation to see where that plant wants to go, or what the plant wants to tell me. And then I'll plant that seed and then try to listen as much as possible to it and try to nurture it into a growing artwork. But that takes a life of its own, so eventually, for me to become a really good artist is to not even make the work. Just be almost like a transformer, and take a high voltage and turn it into a low voltage that you can use at home. So I'm almost a translator of energy into the artwork.

When do you know when you're finished with your artwork or a body of work?

I don't, the work will tell me when it's finished, if I listen to it. I never try to overpower the work, or even try to make it myself. Everything comes from that seed. The plant is going to grow like a kid – you can't control that. You can't control where it goes, to the side or to the left, what color the leaf is, what comes out, does it die? So once the seed is planted, just try to stick with that conversation as much as you can and try to listen to it, and together with meditation, come up with something really unique. But the work makes it its own work. I got that from Philip Guston, he explained it better. He said, when you start as a young artist, everybody's in your studio. Magazines, friends, everybody's with you, everybody wants to be part of it. As you get older people step away, and eventually it's just you with your work, and that's only halfway. Then eventually, he says when you're really good, you're not even making the work. You're physically there making it, but you get to step away. He says, “That's when I know I'm making really good work: when I'm not even there.” When I saw that I was like yes, that's what I'm trying to do, except he explained it better.

Who are your favorite artists?

So, at this moment, it's hard for me to connect with other people since my work is so strange in a way, dealing with death and spells. But Guadalupe Maravilla, that guy's amazing. He’s Mayan, too. He does these shaman kind of sculptures, his work is incredible. He's doing spiritual art that will take you somewhere. Even better, what I respect is that his work heals. He's healing people because he had cancer. He's also doing art with his mystical powers, but his work is very positive.

I'll say Jean-Michel Basquiat, there is no fucking doubt. That guy's incredible, just incredible. Nobody comes close to him in paintings, nobody, because he's also doing spells in a way, there's writing. He puts that energy in those pieces that when you get in front of them, you feel it, right? He's a master at that.

Paul McCarthy, that's the third one. That dude’s work is on another level, and he's nice and nasty, which I like. He's hardcore. Everything he does is really, really getting to me more and more.

What gives you the feeling of butterflies in your stomach?

Oh, anytime I'm in a show. I get it whether I show a tiny piece or a big piece, or a good group show or not so good group show. Anytime somebody takes a look inside your soul it's a bit scary to me. Because I am showing my soul, I'm trying to show what's inside. So yeah, showing my work is still difficult for me. I go to the shows and I'm a great talker, but deep down inside, it's nerve-wracking a little bit, because people can judge you.