AMANDA JOY CALOBRISI

Interview published June 23, 2022

Amanda Joy Calobrisi is an artist, writer and educator living in Chicago, IL. Her paintings are experiential, psychological and inhabited by wise and lyrical feminine figures. Her painted forms reveal themselves through heightened color, loose pattern, and uncouth textures. Dense organic shapes and tangled marks made with loaded brush allow the figures to exist in a field of constant motion despite painting’s persistent stillness. From within these silent cacophonies she asks the viewer to contemplate intimacy, desire, friendship and love.

She has exhibited her work at Western Exhibitions, Chicago, IL., Roots and Culture, Chicago, IL., MiM Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, Co Prosperity Sphere, Chicago, Il, Whitdel Arts, Detroit, MI; Fundación del Centro Cultural del México Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico; Onishi Civic Center Hall, Fujioka, Japan; Naomi Fine Arts, Chicago, IL; Ugly StepSister Gallery, Chicago IL; Unspeakable Projects, San Francisco, CA; and S & S project, Chicago. Her work has been published in New American Paintings.

Amanda received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, a Post-Baccalaureate degree from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston and a Master of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2008. She is a lecturer at The School of the Art Institute where she teaches in the Painting and Drawing department and freelance writer for ADF web magazine, NPO Aoyama Design Forum, Tokyo, Japan.

Hello Amanda! Thanks for joining me for Mint Tea. To begin, what’s your favorite tea?

Okay, so I love tea. I love lots of tea, so I can't really pick a favorite, but this morning, because we're doing this, I broke out this beautiful teakettle that I found. It's from the 1930s. And I made green tea for this occasion – Japanese sencha. So it's not necessarily my favorite, but it's up there. I also go through phases of needing black tea with cream and sugar. So today's a green tea day.

Could you tell me about your background and your practice?

I grew up in Westchester County in New York. I was not an artist at that time, though, I did in first grade make a painting of these trees that were growing out of a body of water, and it won an award. And then on in second grade, I made a drawing of a dog, and that also won an award. But then I went on hiatus for many, many years. Then in college, I started painting a little bit more seriously, but I was a psychology major. I transferred my major from psychology to art, and kind of called myself an artist at that point. Looking back, I can't believe I did, but I did. And I worked in all kinds of media. I started in printmaking and drawing and photography in undergrad, and painting was something I kind of started doing on my own. I went to the University of Massachusetts in Boston, and they had an art major, but their art facilities weren't capable for oil painting. So we didn't do oil painting at school. I did it on my own. So in a way, the painting part of me came from an intuitive place. I never learned how to paint, which I think is part of the reason why I love teaching so much, because I didn't really get that part of it. So after I did a post-bacc at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, I came out here to Chicago, and now I feel like I've returned to doing a little bit of everything again, even though the oil painting thing is the most persistent of all the media.

I'm teaching. I don't typically teach in the spring semester, but I am teaching right now. I typically teach in the fall and summer. In the fall I teach at the School of the Art Institute with their undergrads, and in the summer I typically teach high school students through the Early College Program at SAIC.

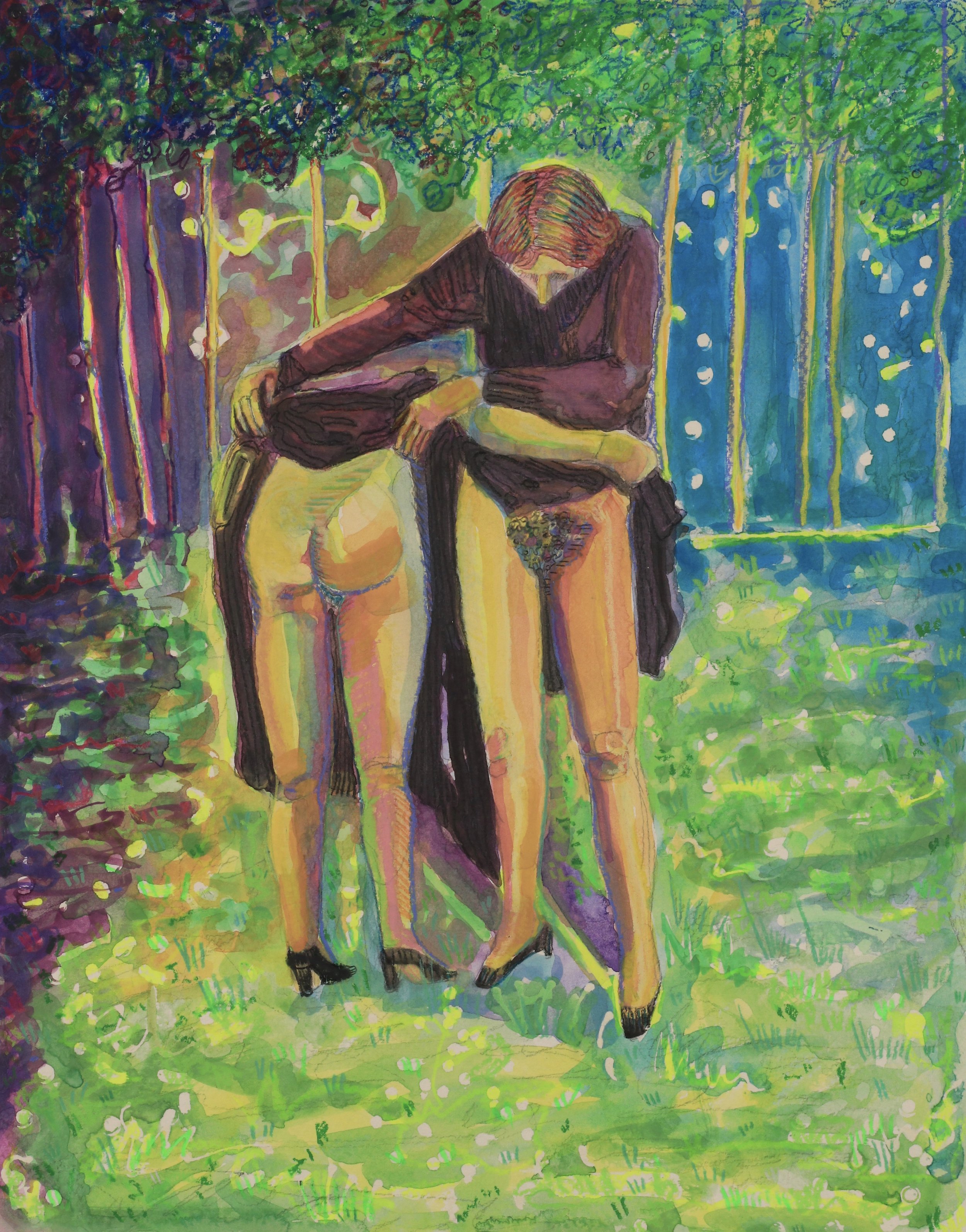

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Double Anasyrma with Cigarette,” 2021, oil on canvas, 53 x 42.5 in.

What projects are you working on right now?

I have two bigger paintings that I'm working on. One of them is about 75% done… let's say that. And then there's another one that is a little bit more done than that. That's primarily what I'm working on right now, two paintings that are part of a bigger series that I've been working on for seven years. The series actually started when I found this image on the internet. I was looking at these Greek sculptures – there was one particular Greek sculpture of a woman lifting her skirt. And in this gesture, which I later learned was called anasyrma, she revealed under her dress, not a vulva, but a penis. I was really fascinated by the sculpture, like, what did it mean, what is it all about? I started doing research on that sculpture. And in that search, I found this image. It was from the early 1930s. And the image was of three women with their backs leaning against the wall, and they had old-style hats on, and they were all three of them lifting their skirts, and looking down at their own bodies, not at each other.

It was such an intriguing photo – it utilized a lot of sort of motifs that I used in my own work in that they had this patterned wallpaper behind them, and the female form in front. There was sort of a psychology to it, because they weren't interacting, they were looking at themselves. I became really fascinated with this one photo. I didn't know anything about it, it was really low quality, when I blew it up to look at it, it was all pixelated, but when it was small, I could see the detail. And I made a painting from that. I just love the idea of it. In combination with the sculpture, in my head, juxtaposing those things just opened this door toward the body of work that I'm still working on, seven years later. So the things that I'm working on right now are connected to this, ongoing thing that has been happening for seven years. Things have happened along the way, but I keep returning to this imagery, and I really think it comes from that photograph and that that sculpture.

I am the most familiar with your oil paintings, drawings and sculptures. Can you talk about how and why you choose to work with the media that you do?

Well, the original decision to work with oil paint was because I wanted to be part of the tradition of painting, and in my mind, oil painting was the original way to go. So, oil painting to me felt like, if I'm going to call myself a painter, then I need to be able to work with that. And even at that time, looking at the people around me, a lot of artists I knew were working in acrylic, and it just seemed like a standard. Of course, over the years, I've learned how to use acrylic to make it the way I want it to be. I had to learn how to use acrylic, so I'm not diehard anymore. When I started, I really felt like I needed to master that medium in order to have the gall to call myself a painter. So oil paint, I prefer to use it, but usually when I'm working on smaller canvases and I want to work more quickly, I will use acrylic paint. The move to clay, started probably seven years ago. I think it really came out of wanting to use a medium that I didn't know anything about, because I was starting to feel like I kind of knew what to expect from oil paint. And I wanted to use a material that I had no expectation of at all, and clay seemed to be the way to go. I kind of want to keep my relationship with clay like that, if possible, to never learn too much about it, because it's a place that I can go when I want something unexpected to happen. And then the drawings, I started drawing when I was having a crazy teaching schedule, where I only had like three hours in the morning to work in my studio. And so I thought, what can I do in three hours that will feel satisfying and not rushed, and drawings really came out of that. I never felt like I was squeezing in a drawing the way I feel like I'm squeezing in painting, if I only have a short amount of time. Because drawings can kind of happen in all kinds of blocks of time, like you can make a ten-minute drawing and be satisfied. A ten-minute painting? No, not for me.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Anasyrma (Nonconformist between Two Trees),” 2021, oil on canvas, 40 x 32 in.

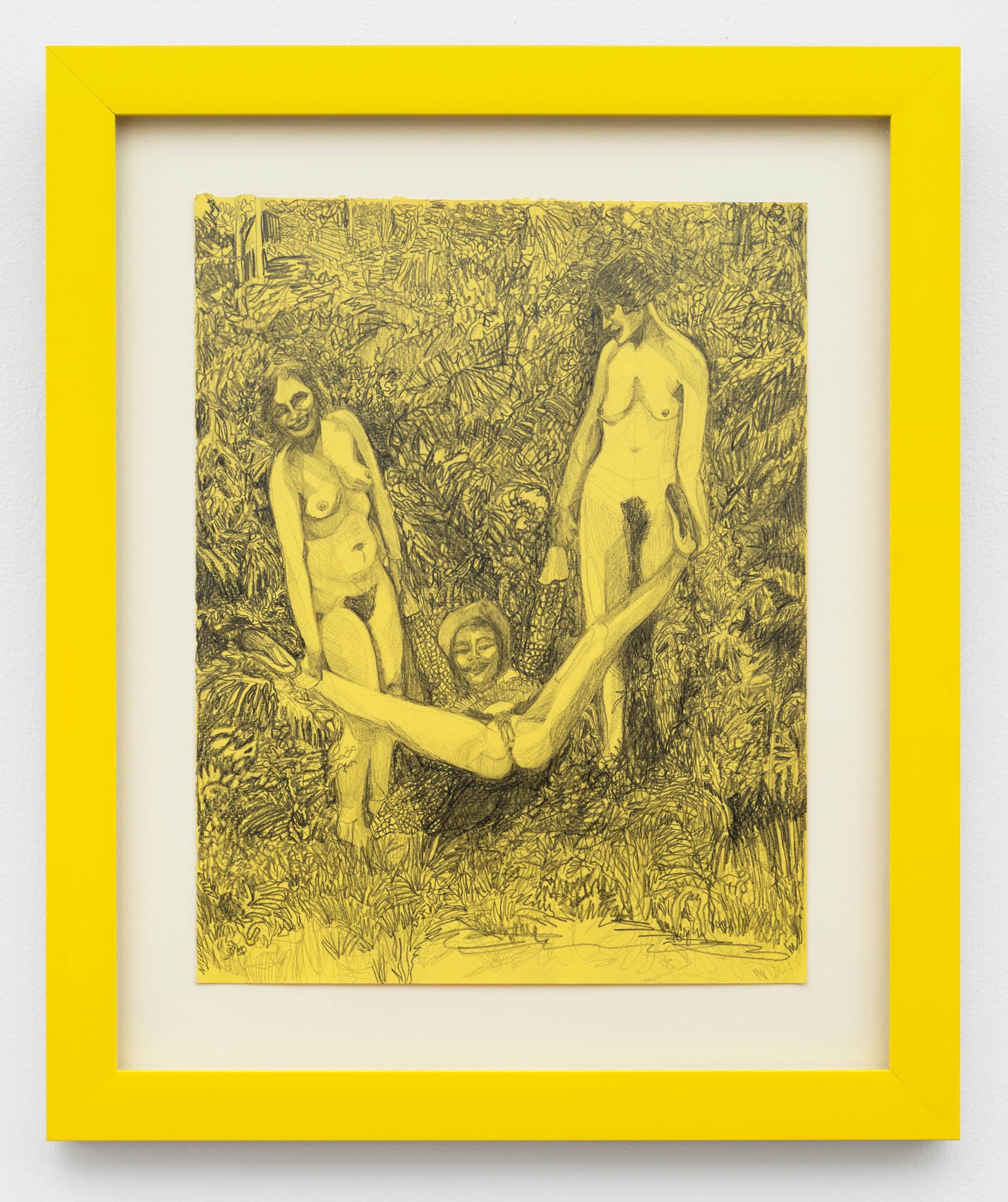

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Are We Having Fun Yet?,” 2020, graphite on yellow paper, 12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in.

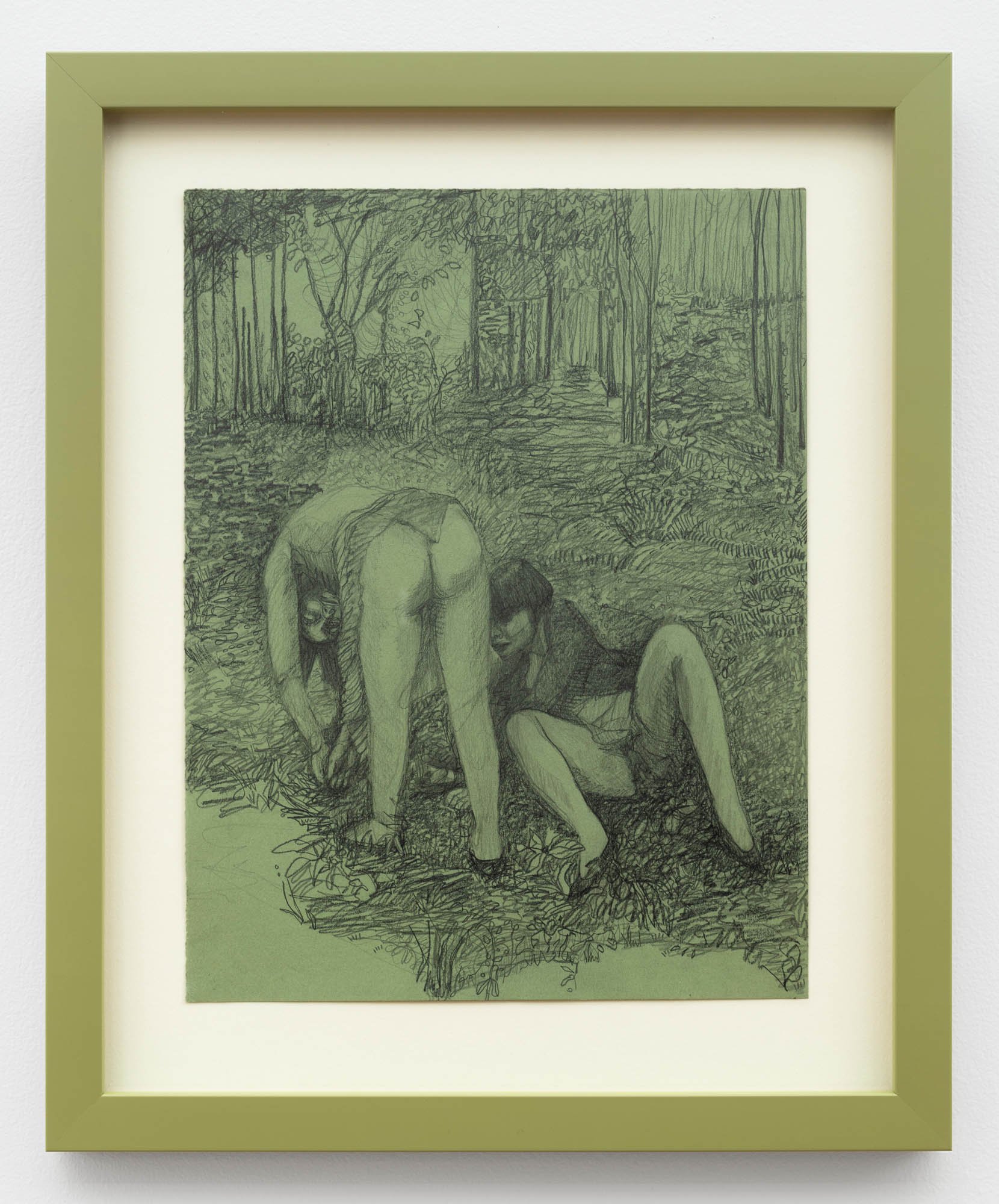

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Urban Foragers,” 2020, graphite on green paper, 12 1/2 x 9 3/4 in.

What is your painting process like? Do you start the painting with a specific image in mind from the beginning or does it evolve organically as you go?

Well, I work from photographs, and for parts of my life. I took the photographs, and I choreographed friends or models, and worked very closely to that photograph, not replicating the photographic quality, but pretty much keeping everything where it was in the photograph. But over the last decade, I feel like that's changed a lot. Now I've been working from found photos and working from photos that were taken in the 1920s and 30s. So I'm kind of given some information, but not the clarity of the technology that we have right now. It leaves space for me to invent a lot. The photographs are also black and white, so I can invent color. Once I switched from taking my own photos to the black and white found photos from this specific time period, it really opened up a door for me to use my imagination more, because I always knew that I was a very imaginative person, but I was kind of trapping myself in this sort of replication of a photograph and leaving no space for imagination at all. So once I kind of made that leap to the black and white photos, it just opened up my ability to experiment, and play, and invent. The photographs that I'm using, I do choose because of the configuration of the figures and the poses and gestures that the people in the photographs are doing, but sometimes I completely invent where they are, like the original photo might be inside a room, and then I put them outside. So the thing that stays the same I would say is the figures’ poses, and then maybe I interject what I'm reading in their faces. So there's a lot more invention now than previously.

What inspires your images?

So the inspiration really comes from, like I said earlier, this meeting of this ancient gesture from the Greek sculpture, but it's even older than that, like, you can find this sacred display, this anasyrma, you can find it in all kinds of cultures, East and West. For example, sheela na gig is an Irish statuary that you'll find in churches. There's a great book, called “Sacred Display,” and it's an encyclopedic collection of statuary in these poses where they're anasyrma, or they're sort of asserting their femaleness. And so I think discovering that very first sculpture and then going through the research of finding other statuary and such from different cultures, was the initial inspiration. Thinking about those references made me look at erotic photography in a different way. So I think that, without the sort of art historical background of sheela na gig and anasyrma, the erotic photography that I'm looking at and making paintings from, wouldn't speak to me in the same way. It's almost like I'm looking at this erotic photography through the lens of ancient female representation.

That initial photograph that I mentioned earlier of the three women and the patterned wallpaper, I ended up finding out who that photographer was. It took a couple of years to bump into it again, and I've been working through his photos for the last seven years. He is a photographer that, for his own personal pleasure, he took photos in a brothel in Paris in the early 1930s. He never wanted to say who he was he remained anonymous. Apparently, the story goes that he sold the photographs to a collector when he was on his deathbed, and he told the collector that he didn't want his name ever to be revealed. So he goes by Mr. X, Monsieur X. And, as an artist, I feel like we're always kind of spinning narratives on top of narratives. So, that was his story, and part of part of me, when I started using his photos a lot, I started thinking, he made himself as anonymous as the girls in the photos, right? Like, these are young women in Paris, working in a brothel, they all have their fake names – which people know, their fake names are written on the backs of the photos – but those aren't their true identities. And I kind of loved that he also didn't reveal his identity. And I kind of imagined – which I don't know, we'll never know if it's true – I kind of felt like he was like leveling the playing field. Like, they don't get to be who they are. So why should I be the artist. But I spun that narrative, you know, he never said that. He probably just didn't want his wife or family to find out that those were his photos, right. But you know, I tried to pull this like, democratic narrative over it all, because it just makes me feel like I'm having a conversation through his photographs, in a way that's more interesting, and I don't know, more motivating. So I love that I don't know who he is, and I think if I knew his name, I wouldn't feel as free to use his photographs.

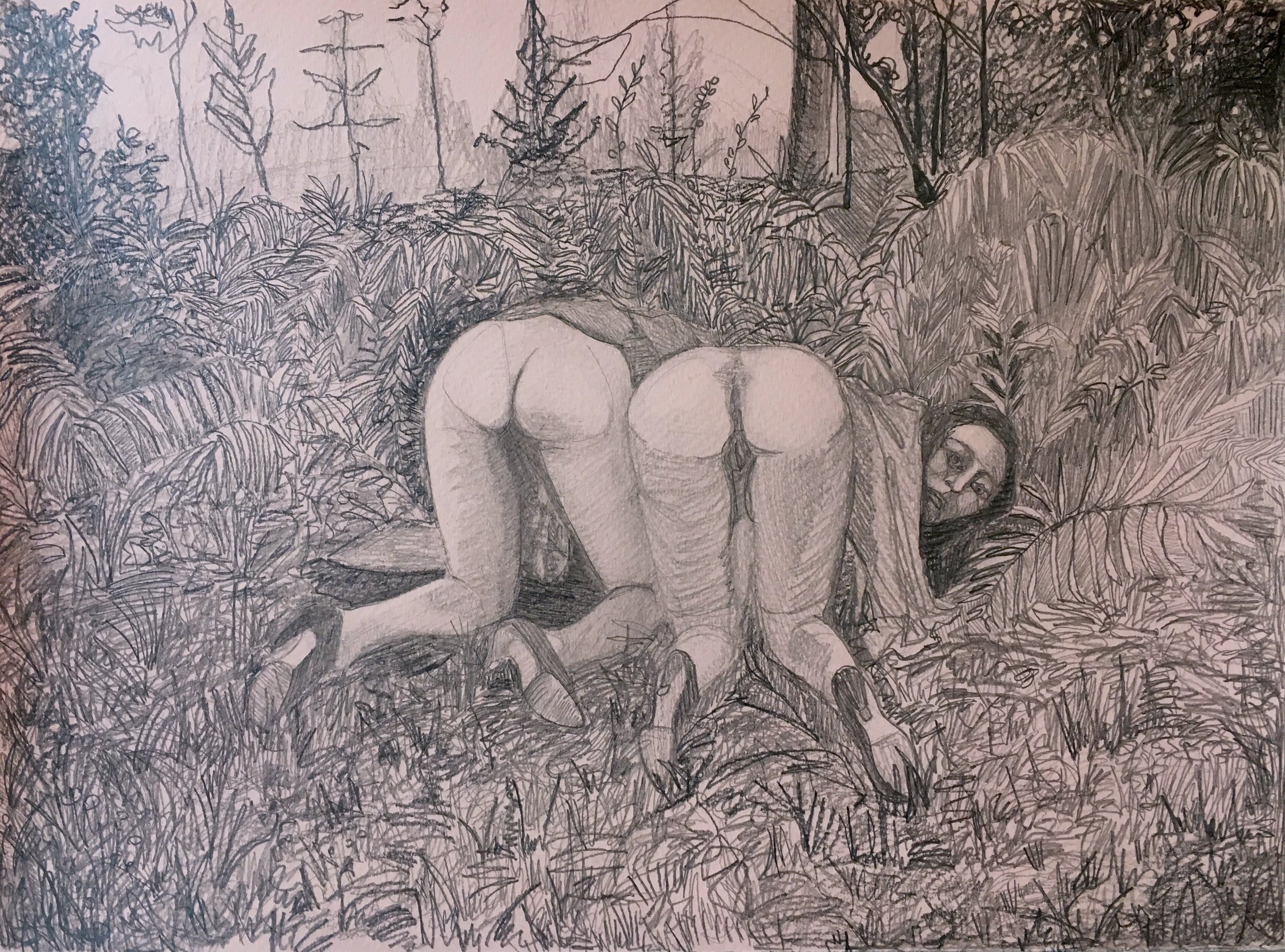

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Comfortable like Cats (Raised Rear Ends),” 2021, graphite on pale pink paper, 9.5 x 12.5 in.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Comfortable like Cats (Raised Rear Ends),” 2021, oil on canvas, 36 x 51 in.

Who are the female figures in your paintings? Do they function as a type of self-portrait or are they something else?

I think that they're just a reflection of all of us who identify as female. I think their femaleness is our femaleness. I think when we look at images of women, we sort of see them as a mirror, so they are a mirror for whoever feels camaraderie with them. I think that I see myself in them a lot, because we share similar bodies, and sometimes I feel like my own face, I don't see my own face in the immediate world around me, but I do find my face in like 1920s Europe. I've always gravitated toward that time period of photography and painting, because I feel like I find my face there. Like, the first period or movement in art that I really fell in love with was German Expressionism. And it really was because I saw women that seemed like my sisters, you know? So in a way, I think the self-portrait is there, even when it's not there. But maybe not always about the visage, or about the body, it could also be about a similar feeling or a similar sort of presentation. But yeah, they are mirrors, but I hope that they're not just a mirror for me, and that other people can look at the paintings and react, or be with the people in the paintings in a way that is like camaraderie. But, I mean, literally, the women are sex workers that worked in one brothel in Paris in the early 1930s. But when they become paintings, I think they become closer to me than the women who are unidentifiable, at this this time.

One of the questions that I feel like I asked myself, because when you're making these kinds of paintings, I feel like you have to keep asking yourself, “What am I doing? I know I'm a woman, and I know that I can talk about the experience of being a woman from the inside, but you still have to ask yourself bigger questions than that, right?” And one of the questions I have is, “Can images of women expressing sexuality be seen affectionately, rather than objectively?” I mean, of course, I want to say yes. But I think every time I make a painting, I kind of have to ask myself, is that what I'm doing right now? And will my answer of yes, be everybody's answer of yes? And I don't think I can hold that responsibility. Like, I don't know. So I feel like, the big thing that I try not to think about, but of course, when I talk to another human being about my art, I have to think about is, how can I construct sort of a new feminist language to talk about these things? And that “how?” isn't going to be solved. Like, the paintings are me questioning how to do that, and I don't know, maybe some of them are doing that better than others? I don't know.

What is your favorite body part to paint?

It's funny, because as soon as I think about that question, I think of knees. I love knees. I love painting knees. I think when I was a little girl, being a young woman, you come up with all sorts of things to be paranoid about your body right away. But one of the first places that I felt really kind of like, vulnerable or sensitive about were my knees. And thinking back, it seems so ridiculous to be self-conscious about your knees, but I felt like my knees were bigger bones than other people and that they looked chunky and weird. I think that that sort of really sad way of thinking about something so not important, kind of led me to thinking about knees in a more deep way than that. I don't know. And I always love looking at the way painters paint knees. They're really interesting parts of the body, if you think about it, because when we're standing, they're almost invisible, and then when we sit, they become so prominent. And knees are really different from person to person. They're one of the hardest parts of the body besides our foreheads, so they're also this protective thing and this bony thing, and so they have interesting structure. I also like painting feet a lot too. I think I like volume. I like bony structure and volume. I like hard, bony, angular things.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Foragers (Hortus Inclusus),” 2021, oil on canvas, 40 x 32 in.

How do you decide on the poses for the figures?

So luckily, the poses are given to me. But I think that in my mind, I have like this huge dictionary of poses that I've seen in paintings and photographs that sort of express or communicate to me. And the photographs, this guy was pretty prolific as a photographer – I actually have two books of his work. They're kind of small, but they were put together by an art historian named Alexandre Depouy – I’ve been in contact with him before, he also owns a antique shop, and he sells some of these photos at the at the antique shop. I have access to a lot of photographs of his through this art historian and also through the two published books, and not all of the photos appealed to me. I'm kind of curating or looking for something specific. And the photographs, I think I'm looking for two things that I can name: one, a sense of agency, or just sort of self-possession. I don't want to use poses where the woman isn't present, like I want the woman to be present in the photo. But the sort of other end of it is, I like when I find a photo of Monsieur X’s that there's a figure sort of removing herself, psychologically, from the sort of theatrical play of the photograph. Maybe one figure is looking out a window when everyone else is performing. So I kind of like that too.

But yeah, there are certain things that I look for in in the photos that maybe go back to self-portraiture, things that I feel, or want to feel. And so I'm looking for things that I recognize, and not every photo has something in it that is recognizable to me. I love awkwardness. I love when women are awkward, and that awkwardness becomes beauty. Especially with a boudoir photo, which these are using the conventions of boudoir photography. In those photos, traditionally women look perfect, and they look like a gift for a man. But these photos, the women, for whatever reasons, they look awkward, and they look playful, and they look like they're having fun. And they're not being “a nude,” they're just very naked, and they're funny. I look at a lot of the photos and I just laugh, like, “What are you guys doing?” And so I think the relationship between the photographer and the women in the photographs is really different than the usual boudoir photo session. Like, these ladies are having fun, and they know each other, and they know this man behind the camera, and so there's something really shed, like there's play involved, even though there's also money being made. And making money is exciting! These women were being paid to have fun in front of the camera, and you really see that. Not all of the women are as generous as others, and not all are as indulgent or funny as others, so there are all these different moods happening in the photographs. I'm just looking for ones that I can communicate with, and then I take that and make that the most apparent thing in the painting, instead of it being something that someone has to search for. So if I see a photo that I find a sort of kooky, amorous situation, when it becomes a painting, the painting should show that right away. The viewer shouldn't have to search for it through a hundred 1920s photographs.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Pissing in the Wind,” 2020, graphite on orchid pink toned paper, 10 1/4 x 9 3/4 in.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Through the Thick and the Thin,” 2020, graphite on cinnabar toned paper, 12 1/2 x 19 1/2 in.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, "Lifting of Skirts (Synchronized Presenters)," 2021, graphite, watercolor, gouache, water-soluble crayons and pencils on paper, 14 x11 in.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, "Smiling with a Fan (Two Nonconformists), " 2021, acrylic on canvas, 10 x 8.5 in.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, "Self Revealer (with Pompom)," 2021, graphite, watercolor, gouache, water-soluble crayons and pencils on paper, 14 x11 in.

Many of the figures seem to be placed in a natural environment filled with grass and trees. What is this location?

So, some of the actual photographs that I'm looking at are placed outdoors. They might be parks or things outside of Paris, where the women were taken on a short trip to do the photograph. And I actually, before I started painting these outdoor images, I was only painting the indoor, more boudoir situations. I started seeing that this guy also did some photos outside, and there was something really interesting about seeing these women who, I think that their poses are really monumental. And then placing those monumental poses outside, it kind of created this perfect setting for focusing on their importance. Like, taking them out of the indoors, out of a domestic room, it kind of freed them from the thing that holds the man in power, because the photographer is inside this little room with these women, and then outside it's like the women kind of own the environment in a different way. I don't know, I actually can't really explain it now that I think about it in words, but I think that just being outside, placing the figures outside just gives them more freedom. Almost like claustrophobia when we're inside, and then this freedom outside. Now, at this point, a lot of the poses that I'm using, the original photos are indoors, and I'm just creating an outdoor environment. So I'm not even looking at an environment that these women were ever in. I'm just imagining you know, some of these locations or I might use photos from my Japan trip, when I was doing some plein air painting there in the mountains, for example. I might either imagine a place or use specific photographs from a place that I've been. So now they're kind of totally collaged together. But yeah, being inside, all of a sudden it became claustrophobic for me to paint it.

Can you talk about any imagery or symbols that you like to work with?

I think that I think that my palette, it's very bold and bright. And I think it has to be because it accompanies imagery that, if it isn't boldly articulated, then I think it's easier to objectify the figures in the paintings. That's my strategy, I can't claim that it works, but it's something that I tried to use to kind of give them some strength, so that when I put the paintings out in the world, hopefully that resonates with the viewer. I think if the colors were muted or less in your face, I think that the figures might come off with less agency or less courage, because I think that they're pretty courageous, the women who posed for these photos. But also in the paintings, I want them to be complex and strong.

What are your favorite colors? Do they find their way into your artworks?

I mean, I think if you look at my paintings, I love all colors. But I love hot colors, like colors that are almost electric, for the paintings. I don't always dress in those colors, but I do find myself drawn to clothing that has similarity to the paintings’ palettes. I worked in vintage for a really long time, and I love vintage clothing, and I feel like the clothes that I own, if not wear, sometimes match the paintings.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Untilted (Paradise),” 2021, clay sculpture

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Nonconformists (Sheela Na Gig),” 2021, clay sculpture

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Backbend Presenter (Sheela Na Gig),” 2021, clay sculpture

I see that you are also working on sculptures. Can you talk about the relationship between your painting practice and your sculptural works? How does working in multiple media affect your practice?

The sculptures, especially the last bunch of them that that I did, I felt like it was sort of like a natural progression. If I was thinking about sheela na gig and thinking about the sort of Venus figures, it only made sense to take the imagery of the paintings and sort of translate them into clay, because the sheela na gigs are like gargoyles that are part of architecture, and the Venus figures are small, hand-sculpted figurines. So it kind of seemed like a logical progression to move some of the imagery from the paintings or some of the poses from the paintings to sculpture. It just made sense, and I want to make more sculptures that play with this sort of sheela na gig meets these Monseiur X photos. I haven't really got there yet, but it's on my very long to do list.

Is there a new medium that you would like to try or to work in more?

Yeah, I one hundred percent, tomorrow would go and do some printmaking, if I had access to it. If someone called up and they were like, “I've got a printmaking studio, come over,” I would be there in a second. I took printmaking classes as an undergrad, and I really didn't know how to draw at that time. I feel like now would be the time to have access to a printmaking studio. So that is definitely next on my list. And I said already my to do list is huge, so I'm not sure when I'm going to get to it, but printmaking for sure.

Where are you located now? Do you think your location influences your practice?

I'm in Chicago. I've been in Chicago since I moved here for grad school. I think anywhere you live or anywhere you stay influences your body of work. I'm actually going on residency next month. I'm going to Italy. I can't wait to just be in another place. It's always exciting, and the reason why I mentioned that is because when you get back home, you appreciate it again. But at this very moment, I feel kind of off my relationship with Chicago. It could be because we're coming out of winter, and so I'm like, “Oh, Chicago, don't even say the word.” But I do look forward to coming back in July and just feeling that love again. And there's a lot of love in Chicago in the summer, there really is. It's like a different country in the summer compared to the winter. But I'm sure it influences me all the time, I'm just kind of lethargic toward it right now.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi in studio

How do you stay connected to your community?

Well, it's been extra hard the last two years, for sure. I feel connected always through teaching. Doing that really allows me to stay connected to the School of the Art Institute and the faculty and students there. Beyond that, in the last two years, it's been really kind of challenging. My partner and I, who is also an artist, when we were finally kind of turning a corner in this pandemic, when we were getting that first vaccine, we came up with an idea to have these monthly salons called Four Penny Salon, where we would invite artists to come and bring a piece of work or a sketchbook or something to share, and come to my studio, I would clean off one big wall on my studio, and we'd hang everything up and just hang out and get used to being around people again, because we were all kind of becoming kind of weird, I think, from not having conversation. And I was weird to begin with, so I mean that in the nicest, nicest possible way. But we were all kind of lonely, but also, like, needed some practice just being around people again. So we started these monthly salons, and it was really great. The first the first one, I think eight people came – it wasn't a big thing. But it was wonderful, and every month, they got a little bit bigger, but they never got too big to feel like a party or just chaos, which was good, because I'm not sure if I'm ready for that yet. At least, not at my house. That that was one way to really stay connected, and also meet new people, because that was the other piece that I really longed for, is just that the world is bigger in Chicago than the School of the Art Institute. There are other artists outside of that, and I want to know who they are and see what they're doing, and just like make that that art world bubble just a bit bigger than it is, especially when you're teaching and part of the School of the Art Institute, because it really is a bubble once you're kind of connected to an institution. So the other idea was to just widen that. And one of the things that I tried to apply to it was that it was interdisciplinary, and all different ages, multigenerational, and just a big diverse group of people, to the best of my ability. And I also had it so that people would bring somebody they knew so that would widen the circle too. We did I think about six of those, and then hopefully we'll return to doing those when I get back from Italy.

What’s your favorite tool?

I would never want to call my cats “tools,” but they really do help in the studio. I love having them here. I have two, Charlotte and then a big boy who is an older guy named Lucien. But yeah, they're not necessarily tools, but they're kind of my muses.

What is the space where you do your work?

My partner and I moved into this space, like during the worst part of the pandemic. It was November, the cases were crazy, and we were looking for an apartment. This new place is really cool. It used to be a beauty parlor with an apartment in the back, so my studio is an old beauty parlor. It still has the mirrors on one side of the wall. And then it has this furniture, where all of the beauty supplies would go, and they look like they're probably from the 40s or 50s, but there's some sort of hardware that looks like it's from the 1930s. So I think that my studio was a hair salon for a very, very long time, all different time periods. The building that we're in the house we're in is from 1888, so it's a very old building, so my studio is an old hair salon, hence calling that our art gathering Four Penny Salon. It's kind of a play on that, and in the basement, we found this old poster from the 1930s for a hair product called Four Penny Hair Tonic. So this studio is in my home, it's a big room that's at the front of the apartment that faces the street.

Amanda Joy Calobrisi, “Pisser (After Rembrant),” 2021, clay sculpture

Do you have any ritual that helps you get into the zone?

Especially lately, I feel like, the majority of the last two years, my work schedule was so open, that I had so much time in my studio, that it almost felt like too much time. I think that those rituals really come out of needing to get to work quickly, because you have X amount of time, and you have to do it. But I've had the privilege of having seemingly too much time, so a lot of those rituals have died out. I think all that really remains for me is just a good hot cup of tea in the morning.

When do you know when you are finished with your artwork or a body of work?

I mean, from our conversation, you can probably tell that the ending of a body of work is really unpredictable for me. When something is going to end and a new thing is going to come in, it feels really out of my hands. It's almost like I think the work just has to tell you that. And I would say the same thing with the work itself. Like, I get really excited that a painting is almost finished, and then usually I will say to my partner, “the painting’s almost finished,” and he just kind of looks at me like, “okay…” and then I spend another year on it. He knows not to believe me, because it's like, I want to be finished with it, but I really love to build a surface, and I can't get the surface that I want without spending an incredible amount of time. And that time can't happen in a two month period because I need breaks and I get tired of building the surface. And so six months is a good amount of time to build a surface, but I'm usually working on at least three paintings at a time, so it becomes more like a year, because I'm going back and forth between this and that. You know, the one privilege of not having gallery representation is that I don't have any deadlines, and that's both a blessing and also a challenge. I feel like I have all the time in the world to work. I'm not sure if I had a deadline if I would work faster, if I would stay at the same pace. But when something is done, I just know, and sometimes I'm wrong and then I go back and I work more.

Who are your favorite practicing artists?

I really want to see more Salman Toor and more Kyle Staver. Both of those guys are New York artists. As far as as like my peers and younger artists that I peep on Instagram, there's a couple of British artists, Haley Craw and Liorah Tchiprout. I follow both of them on Instagram and I love their work. I bought a drawing from Haley Craw some time during this pandemic, it was really cool to see her work in person. And then other artists that are my peers that I know and love like Chinatsu Ikeda is a friend of mine who is an artist, and I'm going to see her in Italy which is very cool. Also, Stacy Howe, I went to undergrad with her. She does amazing collages and drawings. I could go on and on about artists that I love and want to support but that's a handful.

What gives you the feeling of butterflies in your stomach?

I almost feel like I live in a state where my stomach is always in butterflies, but I would say no matter how many years I teach, I always feel that way the first day of school. Always, I feel that. But yeah, I am a nervous person, so that's a pretty standard feeling for me. It's almost like when I don't feel it, that I'm aware of it.